Sparrow’s Song

Mostly Quiet

January, so far, has been bereft of snow with none of that softness to cover the bleached grass, the rutted earth. Bare trees etch the sky with their tremulous script. The sun is thin. When the wind picks up, the old windows rattle, keeping time. But mostly, it is quiet here in my gray little village with its Main Street ending in the sea.

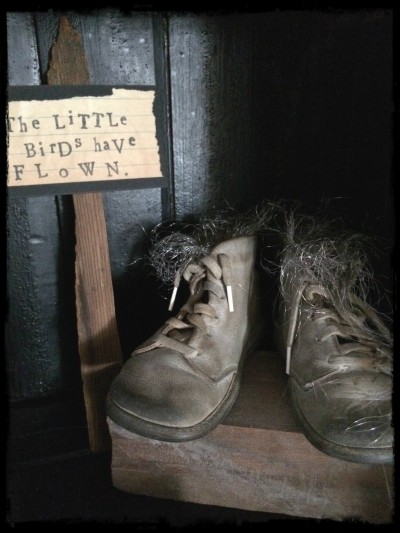

I haven’t settled into January yet. Even mid-month, I’m still living the tinsel-packed pace of December. Still looking at an overloaded calendar. Still sensing that something is chasing me, and looking over my shoulder, I see nothing, hear nothing, but feel its quick, dry breath.

When I think of the January of my dreams, I think of a month of eternal days and long dark nights with only the stars and the wind for company. I think of a sameness, of an uneventfulness as comforting as a gray flannel blanket. This sameness is good for me, I think, though for others, it is stultifying, drab, depression-inducing even. My friends long for cities, for palm trees, for parties, for something to look forward to. They miss December and its red dresses and glittery shoes, its sparkling lights and silver bowls of eggnog, its mad-cap pace.

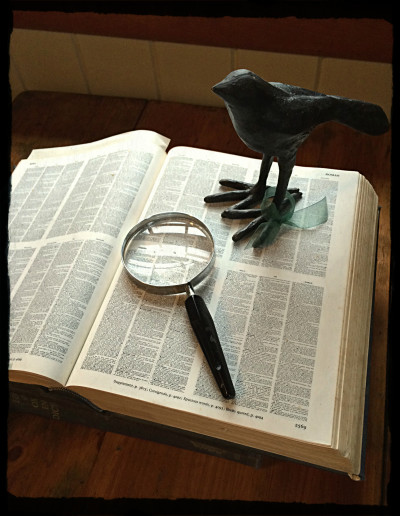

“I dwell in possibility,” Emily Dickinson wrote. She was speaking of poetry, I believe, but with its absence of distraction, there is possibility everywhere in January. Possibility in the making of soup, of soda bread, of an orderly sock drawer, of a fire in the hearth, of the knowledge of a brand-new word, of a walk at dusk with the sky all violet and purple, with frozen blue-striped sheets on the line, with the single flash of a cardinal, a conversation of sister crows in the old pine tree across Main Street.

I long for January and wonder if I’ll find it before it’s over. I tell myself to slow down. If I only have an hour before dashing out again then stretch that hour all the way into a lingering afternoon. Read one poem. Mix up the soda bread and bake it later. Toss some rusty pieces of metal on the worktable and see if they assume a shape, whisper the first words of a story. At least start on the sock drawer. Or just look at the sky for long minutes. Stand in the pale sun that comes in the kitchen door and let it soak into my back…so that when I look over my shoulder, there is nothing there but a January morning.

The dry breath is a sparrow’s song.